CHAPTER IX

When I was in the service of the Turks I frequently amused myself in a

pleasure-barge on the Marmora, which commands a view of the whole city

of Constantinople, including the Grand Seignior's Seraglio. One

morning, as I was admiring the beauty and serenity of the sky, I

observed a globular substance in the air, which appeared to be about

the size of a twelve-inch globe, with somewhat suspended from it. I

immediately took up my largest and longest barrel fowling-piece, which

I never travel or make even an excursion without, if I can help it; I

charged with a ball, and fired at the globe, but to no purpose, the

object being at too great a distance. I then put in a double quantity

of powder, and five or six balls: this second attempt succeeded; all

the balls took effect, and tore one side open, and brought it down.

Judge my surprise when a most elegant gilt car, with a man in it, and

part of a sheep which seemed to have been roasted, fell within two

yards of me. When my astonishment had in some degree subsided, I

ordered my people to row close to this strange aërial traveller.

I took him on board my barge (he was a native of France): he was much

indisposed from his sudden fall into the sea, and incapable of

speaking; after some time, however, he recovered, and gave the

following account of himself, viz.: "About seven or eight days since,

I cannot tell which, for I have lost my reckoning, having been most of

the time where the sun never sets, I ascended from the Land's End in

Cornwall, in the island of Great Britain, in the car from which I have

been just taken, suspended from a very large balloon, and took a sheep

with me to try atmospheric experiments upon: unfortunately, the wind

changed within ten minutes after my ascent, and instead of driving

towards Exeter, where I intended to land, I was driven towards the

sea, over which I suppose I have continued ever since, but much too

high to make observations.

"The calls of hunger were so pressing, that the intended experiments

upon heat and respiration gave way to them. I was obliged, on the

third day, to kill the sheep for food; and being at that time

infinitely above the moon, and for upwards of sixteen hours after so

very near the sun that it scorched my eyebrows, I placed the carcase,

taking care to skin it first, in that part of the car where the sun

had sufficient power, or, in other words, where the balloon did not

shade it from the sun, by which method it was well roasted in about

two hours. This has been my food ever since." Here he paused, and

seemed lost in viewing the objects about him. When I told him the

buildings before us were the Grand Seignior's Seraglio at

Constantinople, he seemed exceedingly affected, as he had supposed

himself in a very different situation. "The cause," added he, "of my

long flight, was owing to the failure of a string which was fixed to a

valve in the balloon, intended to let out the inflammable air; and if

it had not been fired at, and rent in the manner before mentioned, I

might, like Mahomet, have been suspended between heaven and earth till

doomsday."

The Grand Seignior, to whom I was introduced by the Imperial, Russian,

and French ambassadors, employed me to negotiate a matter of great

importance at Grand Cairo, and which was of such a nature that it must

ever remain a secret.

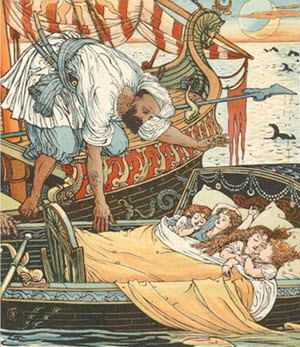

I went there in great state by land; where, having completed the

business, I dismissed almost all my attendants, and returned like a

private gentleman; the weather was delightful, and that famous river

the Nile was beautiful beyond all description; in short, I was tempted

to hire a barge to descend by water to Alexandria. On the third day of

my voyage the river began to rise most amazingly (you have all heard,

I presume, of the annual overflowing of the Nile), and on the next day

it spread the whole country for many leagues on each side! On the

fifth, at sunrise, my barge became entangled with what I at first took

for shrubs, but as the light became stronger I found myself surrounded

by almonds, which were perfectly ripe, and in the highest perfection.

Upon plumbing with a line my people found we were at least sixty feet

from the ground, and unable to advance or retreat. At about eight or

nine o'clock, as near as I could judge by the altitude of the sun, the

wind rose suddenly, and canted our barge on one side: here she filled,

and I saw no more of her for some time. Fortunately we all saved

ourselves (six men and two boys) by clinging to the tree, the boughs

of which were equal to our weight, though not to that of the barge: in

this situation we continued six weeks and three days, living upon the

almonds; I need not inform you we had plenty of water. On the forty-

second day of our distress the water fell as rapidly as it had risen,

and on the forty-sixth we were able to venture down upon /terra

firma/. Our barge was the first pleasing object we saw, about two

hundred yards from the spot where she sunk. After drying everything

that was useful by the heat of the sun, and loading ourselves with

necessaries from the stores on board, we set out to recover our lost

ground, and found, by the nearest calculation, we had been carried

over garden-walls, and a variety of enclosures, above one hundred and

fifty miles. In four days, after a very tiresome journey on foot, with

thin shoes, we reached the river, which was now confined to its banks,

related our adventures to a boy, who kindly accommodated all our

wants, and sent us forward in a barge of his own. In six days more we

arrived at Alexandria, where we took shipping for Constantinople. I

was received kindly by the Grand Seignior, and had the honour of

seeing the Seraglio, to which his highness introduced me himself.