Legands of the Jews > Volume 3 >

THE BLASPHEMER AND THE SABBATH-BREAKER

When Israel received the Torah from God, all the other nations envied them and said: "Why were these choosen by God out of all the nations?" But God stopped their mouths, replying: "Bring Me your family records, and My children shall bring their family records." The nations could not prove the purity of their families, but Israel stood without a blemish, every man among them ready to prove his pure descent, so that the nations burst into praise at Israel's family purity, which was rewarded by God with the Torah for this its excellence. [448]

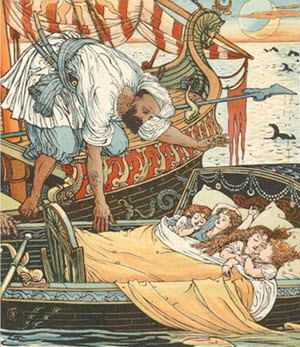

How truly chastity and purity reigned among Israel was shown by the division of the people into groups and tribes. Among all these thousands was found only a single man who was not of pure descent, and who therefore at the pitching of the standards could attach himself to none of the groups. This man was the son of Shelomith, a Danite woman, and the Egyptian, [449] whom Moses, when a youth of eighteen, had slain for having offered violence to Shelomith, the incident that had necessitated Moses' flight from Egypt. It had happened as follows: When Moses came to Goshen to visit his parents, he witnessed how an Egyptian struck an Israelite, and the latter, knowing that Moses was in high favor at Pharaoh's court, sought his assistance, appealing to him with these words: "O, my lord, this Egyptian by night forced his way into my house, bound me with chains, and in my presence offered violence to my wife. Now he wants to kill me besides." Indignant at this infamous action of the Egyptian, Moses slew him, so that the tormented Israelite might go home. The latter, on reaching his house, informed his wife that he intended getting a divorce from her, as it was not proper for a member of the house of Jacob to live together with a woman that had been defiled. When the wife told her brothers of her husband's intentions, they wanted to kill their brother-in-law, who eluded them only by timely flight. [450]

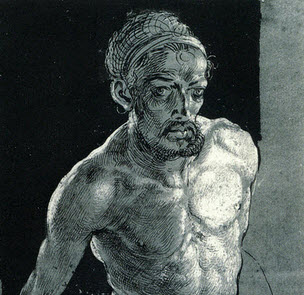

The Egyptian's violence was not without issue, for Shelomith gave birth to a son whom she reared as a Jew, even though his father had been and Egyptian. When the division of the people according to the four standard took place, this son of Shelomith appeared among the Danites into whose division he meant to be admitted, pointing out to them that his mother was a woman of the tribe of Dan. The Danites, however, rejected him, saying: "The commandment of God says, 'each man by his own standard, with the ensign of his father's house.' Paternal, not maternal descent decides a man's admission to a tribe." As this man was not content with this answer, his case was brought to Moses' court, who also passed judgement against him. This so embittered him the he blasphemed the Ineffable Name which he had heard on Mount Sinai, and cursed Moses. He at the same time ridiculed the recently announced law concerning the shewbread that was to be set on the table in the sanctuary every Sabbath, saying: "It behooves a king to eat fresh bread daily, and no stale bread." [451]

At the same time as the crime blasphemy was committed by the son of Shelomith, Zelophehad committed another capital crime. On a Sabbath day he tore trees out of the ground although he had been warned by witnesses not to break the Sabbath. The overseers whom Moses had appointed to enforce the observance of the Sabbath rest seized him and brought him to the school, where Moses, Aaron, and other leaders of the people studied the Torah.

In both these cases Moses was uncertain how to pass judgement, for, although he knew that capital punishment must follow the breaking of the Sabbath, still the manner of capital punishment in this case had not yet been revealed to him. Zelophehad was in the meantime kept in prison until Moses should learn the details of the case, for the laws says that a man accused of a capital charge may not be given liberty of person. The sentence that Moses received from God was to execute Zelophehad in the presence of all the community by stoning him. This was accordingly done, and after the execution his corps was for a short time suspended from the gallows. [452]

The sin of the Sabbath-breaker was the occasion that gave rise to God's commandment of Zizit to Israel. For He said to Moses, "dost thou know how it came to pass that this man broke the Sabbath?" Moses: "I do not know." God: "On week days he wore phylacteries on his head and phylacteries on his arm to remind him of his duties, but on the Sabbath day, on which no phylacteries may be worn, he had nothing to call his duties to his mind, and he broke the Sabbath. God now, Moses, and find for Israel a commandment the observance of which is not limited to week days only, but which will influence them on Sabbath days and on holy days as well." Moses selected the commandment of Zizit, the sight of which will recall to the Israelites all the other commandments of God. [453]

Whereas in the case of the Sabbath breaker Moses had been certain that the sin was punishable by death, and had been certain that the sin was punishable by death, and had been in doubt only concerning the manner of execution, in the case of the blasphemer matters were different. Here Moses was in doubt concerning the nature of the crime, for he was not even sure if it was at all a capital offence. Hence he did not have these two men imprisoned together, because one of them was clearly a criminal, whereas the status of the other was undetermined. But God instructed Moses that the blasphemer was also to be stoned to death, and that this was to be the punishment for blasphemers in the future. [454]

There were two other cases beside these two in Moses' career on which he could not pass judgement without appealing to God. These were the claims of Zelophehad's daughters to the inheritance of their father, and the case of the unclean that might not participate in the offering of the paschal lamb. Moses hastened in his appeal to God concerning the two last mentioned cases, but took his time with the two former, for on these depended human lives. In this Moses set the precedent to the judges among Israel to dispatch civil cases with all celerity, but to proceed slowly in criminal cases. In all these cases, however, he openly confessed that he did not at the time know the proper decision, thereby teaching the judges of Israel to consider it no disgrace, when necessary, to consult others in cases when they were not sure of true judgement. [455]