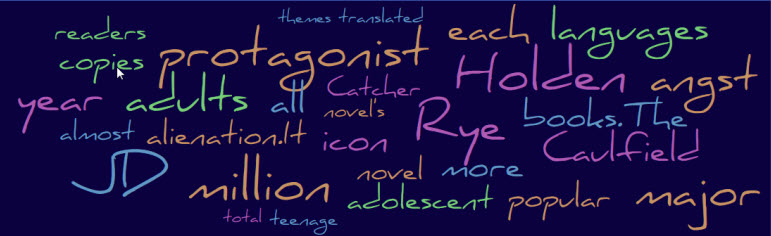

How the War Shaped Salinger's Classic Catcher in the Rye

The Catcher in the Rye

Jerome David Salinger was born to a Jewish father and Scottish mother on January 1, 1919 in New York City. Like many of the characters he would come to create, he was a precocious child. Despite this he flunked out of the McBurney School in New York, and thus the decision was made by his parents to send him to Valley Forge Military Academy in Pennsylvania. After his graduation he attended New York University for a year before traveling to Europe, upon his father's encouragement, to learn about language and business. After spending most of his time in Vienna, he traveled back to the United States to enroll in Ursinas College in Pennsylvania. He then returned to New York where he took night classes at Columbia University where he met a professor by the name of Whit Burnett. Burnett was also an editor of Story magazine, which featured short stories, and a great source of encouragement in Salinger's development as a young writer. Soon Salinger found himself published in not only Story, but in Collier's and The Saturday Evening Post, all of which were highly regarded publications. It was at this critical moment of finding a voice as a writer that Salinger became a soldier in the United States military, leading him to the experiences that would create the mold from which all of his most notable characters and stories would arise.

When Salinger landed at Utah Beach in Normandy on D-day as part of the 4th detachment of the Counter Intelligence Corps, he had in his possession six unpublished stories featuring the Caulfield family. These six stories, although they would come to change as much as Salinger himself, would form the basis of his most famous work, Catcher in the Rye. The icon of the teenage experience, Holden, had been created years prior to his deployment in an experimental story entitled Slight Rebellion Off Madison. Salinger described the piece as "a sad little comedy about a prep school boy on Christmas vacation," and admitted its central character had been modeled after his own personality. His mentor, Burnett, had since encouraged him to create a novel surrounding the character. Salinger, having never attempted anything of considerable length before, decided he would be more comfortable creating the story in individual pieces, ultimately nine altogether. Those initial six that he carried with him through the war, as though they afforded him some kind of extra protection, would be constantly adjusted as he and Holden grew together through the most traumatic experiences of his life.

Fighting their way through the beaches of Normandy, Salinger and his detachment joined the 12th Infantry Regiment. Over the course of the next twenty-six days they would suffer a great number of casualties, losing nearly a third of their force. But they pushed on, and when the Germans surrendered Paris in late August of 1944, it was the 12th's orders to flush out resistance. As intelligence officers, it was Salinger and friend John Keenan's duty to search out Nazi collaborators amongst the French. On one particularly unsettling occasion when they had detained one such individual, an angered mob took the person away by force. Salinger and Keenan, choosing not to fire into crowd, watched them beat the man to death.

Catcher in the Rye - A Rebellion Born Out of the Chaos of World War 2

Salinger's short time in Paris was not completely filled with tragedy though. It was during this time that he made a most important connection with fellow writer Ernest Hemingway, who was serving as a correspondent during the war. Salinger found Hemingway at the Ritz, where they shared a drink and discussed their craft. Hemingway was even familiar with Salinger's writing, and when pressing him for new work, Salinger located a copy of his recently published The Last Day of the Last Furlough, to which Hemingway responded enthusiastically. Although their writing styles differed ideologically, and Hemingway's persona was disagreeable to Salinger, he found him in person to be a kind and gentle man. They would grow fond enough of each other that Salinger referred to him as "Papa" and relied on their friendship and correspondence throughout the war and beyond.

After the liberation of Paris, the Allied forces were to move into Germany, and it was Salinger's division that was amongst the first to do so. They were tasked with clearing out the German resistance in the Hürtgen Forest, which would later become known as one of the more unfortunate decisions of the war. The forest was, unexpectedly, heavily fortified. As a result it became a nightmare scenario of overhead explosions raining down shrapnel and foliage, and the unrelenting harshness of the elements, an intolerable combination of wet and cold, creating a mass of casualties. Most who experienced it would never speak of it again. But despite one of the bleakest moments of his tour of duty, Salinger, as always, persisted in his writing efforts all the while. A fellow intelligence officer later recalled an instance of their unit incurring heavy fire and, as they took cover, caught sight of Salinger typing away underneath a table. The terrible conditions he faced would seem only to fuel his urgency.

The horrors of war had still yet another gruesome facet to present to Salinger's ever-battered psyche. As an intelligence officer it was one of his unit's duties to immediately head towards areas suspected of holding concentration camps. After overtaking the city of Rothenberg, Salinger and the 12th Regiment found themselves in just such an area. They had arrived at the location of one of the most infamous and vast system of camps, the Dachau complex. Salinger was as notable later in life for being tight-lipped about his experiences as he was for his reclusive nature. He even stated through a character in The Last Day of the Last Furlough, "I believe in killing Nazis and Fascists and Japs, because there's no other way that I know of. But I believe, as I've never believed in anything else before, that it's the moral duty of all the men who have fought and will fight in this war to keep our mouths shut, once it's over, never again to mention it in any way." Despite his penchant for terseness, he would later tell his daughter in regards to his experiences in Dachau, "You could live a lifetime and never really get the smell of burning flesh out of your nose."

Catcher in the Rye Summary

The psychological impact of the things he saw during the war took a severe toll on Salinger. Upon the German army's surrender, as the world celebrated, Salinger found himself alone with his pistol, contemplating the feeling of shooting his own hand. Recognizing the fragile state of his mind he decided to seek immediate help. He checked himself into a hospital in Nuremburg where he would be treated for posttraumatic stress disorder. During his time there he wrote a letter to Hemingway, telling him he had been in an "almost constant state of despondency." He also mentioned that he had responded sarcastically to all of the hospital staff's various questions with the exception of one. When questioned whether or not he liked the army, he responded straightforwardly with a yes, fearing that a psychological discharge would lend an unwelcome angle of discussion concerning his yet to be published novel.

When Salinger returned from Europe he immediately threw himself right back into his work, producing a number of short stories. It is revealing of the man's state of mind at the time that the first story he wrote was I'm Crazy. It was the first story to feature Holden from a first person perspective and would later be incorporated into his first and only novel, along with the six pieces he carried with him through the war. The Catcher in the Rye, woven together from all the revised versions of these stories, was published in 1951. Holden Caulfield's journey all the way from Slight Rebellion Off Madison and subsequent transformation into the central character of Salinger's most celebrated work reflects the author's struggle to deal with personal anguish stemming from the unfathomable horrors that touched him so directly during the war. Perhaps it was Salinger's freeing of a character he had taken so long to shape that allowed him his own personal liberation. Although he would eventually stop publishing altogether, choosing to lead a more private life, he would never stop writing. Withholding the bulk of his later work for a posthumous release, his readers can only speculate on what insights the coming years might reveal.