A Confederacy of Dunces: The Classic Novel Nearly Lost to History

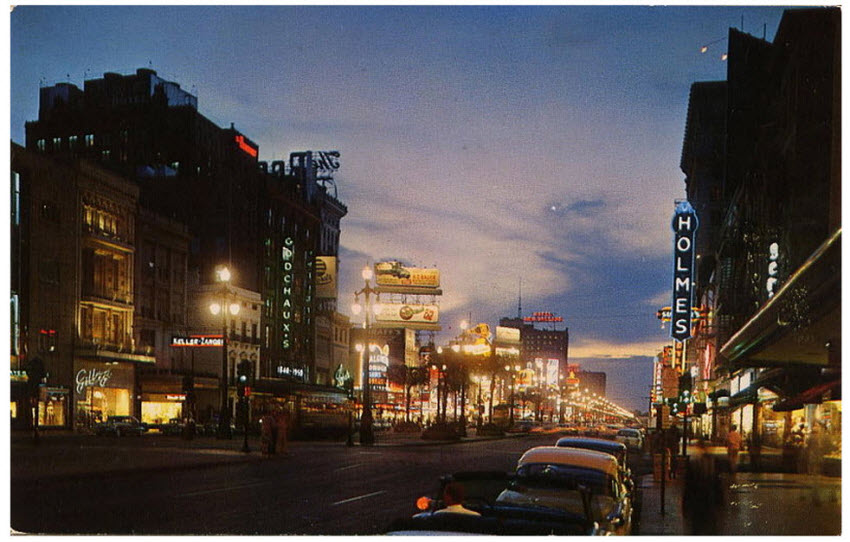

John Kennedy Toole, born, raised and educated in New Orleans, perhaps captured the city’s unique cultural nuances in a manner more profound than any other author ever has or will. A Confederacy of Dunces and the colorful characters therein are as delightfully strange and unpredictable as the Crescent City itself. At the center of the story is Ignatius J. Reilly, a picaresque anti-hero who is one very large man-child against the world. Surrounded by a cast of outlandish characters that are all, to his mind, constantly committing grave offenses against taste and decency, he embarks on a series of misadventures from various states of employment to political activism. The novel, a somewhat crude but beloved masterpiece often considered a work of genius, was the recipient of the Pulitzer Prize the year after it was published. The path to its publication, however, is arguably as interesting and tragic as the novel itself.

Toole’s upbringing would be shaped by many factors, but not least of all was the influence of his mother, Thelma. Her narcissism fueled a growing resentment toward his father for failing to deliver them to a place of distinction and notoriety. Not only did this in and of itself have a profound effect on Toole, but he was also tasked from childhood to be the center of attention for his mother’s various guests. Throughout his life, Thelma would nurture his creativity just as she would push her ambitions onto him, creating a pressure to succeed. She encouraged him to take up stage performance at the young age of ten. This would contribute to his ability later in life to entertain and easily win the affections of those around him, all the while struggling to form intimate relationships.

A precocious child, Toole skipped a couple of grades and graduated high school early, at sixteen years of age. That same year he’d also written his first novel, entitled The Neon Bible, which he himself would later consider adolescent, and a failure. It would eventually come to be published many years after A Confederacy of Dunces became well known. He enrolled on a scholarship at Tulane University in New Orleans, graduating four years later with honors and receiving an English degree. He was then invited to attend Columbia University in New York through the Woodrow Wilson Fellowship where he earned his master’s degree after only one year. Perhaps because it was such a great distance from the troubles of his home life, he set for himself a goal to return. In the meantime he returned to Louisiana, but instead of moving back to New Orleans, he became an assistant professor in the heart of Cajun country at the Southwestern Louisiana Institute, which soon after became the University of Southwestern Louisiana, and is presently the University of Louisiana at Lafayette. Again, his wit and his innate ability to entertain quickly garnered him a fair amount of popularity, and those who knew him well described his time there as likely being one of the happiest years of his life. It was there, also, that he would meet Bob Byrne, a professor of English who would come to be quite influential to the character of Ignatius J. Reilly.

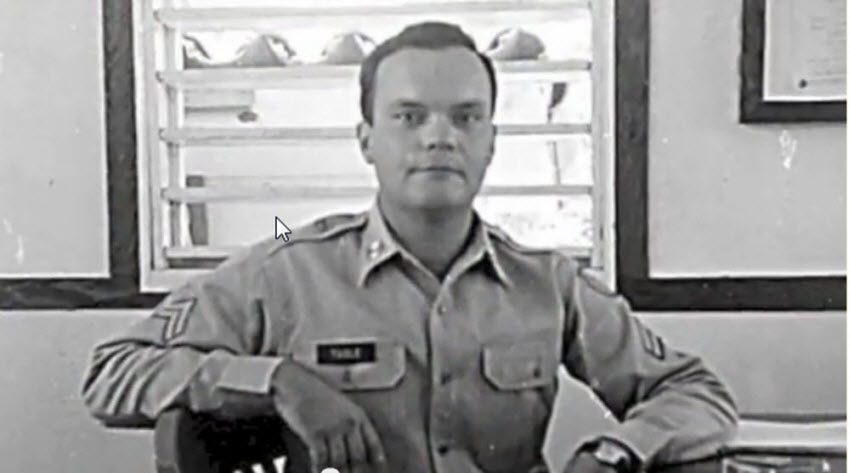

John Kennedy Toole During His Army Service, When He Wrote Confederacy of Dunces

As his year in south central Louisiana drew to a close he was offered a teaching position at Hunter College in New York, which he gladly accepted, becoming the youngest professor to teach there at only twenty-two years old. He simultaneously enrolled in the P.hD program at Columbia University, although he would never get to finish his education there. His studies were interrupted when he was drafted to the military and stationed in San Juan, Puerto Rico, where he resumed his role as an English teacher. Aside from the oppressive heat, of which he frequently complained, life there was mostly calm aside from a little hiccup in international affairs that came to be known as the Cuban Missile Crisis. It was also at some point during his service that he learned of the suicide of Marilyn Monroe. He was not only an enthusiast of her work in film, but he also had an admitted obsession with her, and was profoundly affected by her death. Despite these tumultuous events, Toole was successful at his post, rising through the ranks high enough to be granted a private office. It was in that office that he would begin writing A Confederacy of Dunces on a typewriter borrowed from friend and fellow writer David Kubach. He’d spend much of his remaining time confined there, immersed in his work, until being discharged. He returned home to an ailing father and his parents’ considerable financial difficulties.

A Confederacy of Dunces: One of the Most Realistic Depictions of New Orleans and Its People

Despite his troubles, Toole had a completed manuscript in hand, and was optimistic. He was certain of its value and he believed he’d soon have it published, alleviating his financial concerns and freeing up his time to pursue his dreams of writing. He sent the manuscript to Simon & Schuster, where it came to the attention of Robert Gottlieb. Gottlieb, who had previously worked with Joseph Heller on Catch-22 as well as various other notable authors, seemed enthusiastic about the book. But he informed Toole that he was not able to publish it as it was, and encouraged him to make revisions. Thelma, who considered them a corruption of her son’s work of genius, would later destroy those revisions. Toole and Gottlieb’s correspondence continued for two years, but nothing ever came of it, and despite Gottlieb’s encouragement and enthusiasm to review any of Toole’s new writing, Toole became despondent. He ultimately decided that if he could not have his masterwork published at Simon & Schuster as he intended it, he did not care to have it published anywhere. He boxed it up and placed it atop an armoire in the home of his parents.

Confederacy of Dunces || Summary and Analysis

Toole, who had been teaching at Dominican College, an all female Catholic school in New Orleans, enrolled In the Ph.D program at his former alma mater, Tulane. During this time, those closest to him noticed he was becoming increasingly frustrated and paranoid. He made claims of persecution, which happened to be a frequent complaint of the grand comic figure that was Ignatius J. Reilly. He also attempted to make a strange sort of peace with his failure, making embellished rationalizations by stating that he could no longer reside in New Orleans if the book had ever been published since it was so savage in its satire. Despite all the various influences Toole drew upon, it was evident to those who knew him best that many of Ignatius J. Reilly’s traits had a foundation in Toole’s own personality. Eventually his once comedic performance styled lectures at Dominican College became ever more tainted with anger. Finally he reached a point of frustration that brought out an outburst of wild ranting during a graduate course at Tulane. He walked out, never to return.

With his mental condition deteriorating he developed a preoccupation with Biloxi, a place he had been fond of in his earlier college days. He wrote letters to friends, telling them how this place he once loved wasn’t the same to him. On a visit from Madison, Wisconsin, his old army friend David Kubach rode down to Biloxi with him, where he stopped at a nondescript spot along the coast. Kubach thought nothing of it at the time. A breaking point came when, upon an argument with his mother, he abandoned his typically strict adherence to the obligations of caring for his family and set out on the road. Withdrawing a large amount of money from his bank account, he set out for California. Not much is known about his travels during this time, but receipts were found indicating that he had journeyed all the way back east to visit Andalusia, the home of Flannery O’Conner, whom he idolized. Whatever he found while he was out on the road was apparently not enough to ease the burdens he faced. He never made it back to his home in New Orleans.

In the spring of 1969, upon reaching Biloxi, he could go no further. In the same spot he had once brought his friend, David Kubach, Toole ran a hose from the exhaust pipe into his car window and sat there until the fumes overcame him, ending his life. A final note to his parents was given to Thelma, who burned it, saying it was full of horrible things. By some accounts there were other writings on the seat of his car, perhaps a third novel that he may have been working on, which would have been stored in the Biloxi police department only to be to swept away by Hurricane Camille soon after. Shamed by the suicide, he was shunned by his extended family. At his funeral there were only his parents and his childhood nanny in attendance.

Several years later his mother found the dirty, battered manuscript in the box atop the armoire. It became her sole mission. She diligently sent it out, and subsequently received it a little more worn each time from many different publishers. Finally Thelma’s persistence found her calling, writing, and eventually bringing the novel directly to the desk of author Walker Percy, who was teaching a course at Loyola College. Percy, who could not bring himself to refuse her in person, only hoped that the manuscript would be unremarkable enough that he could toss it aside after a few pages without any qualms. To his amazement, he found himself captivated, and upon completing it decided to take its publication into his own hands. After several more years of effort, it found a home at Louisiana State University Press in 1980. A year later, Toole was posthumously awarded the Pulitzer Prize. With more than a million copies sold, printed in more than a dozen languages, its author’s tragic end is deeply saddening, but his artistry will always be fondly remembered in the hearts and minds of those who have come to love an almost forgotten masterpiece.