CHAPTER XIII A TRIP TO THE NORTH

We all remember Captain Phipps's (now Lord Mulgrave) last voyage of

discovery to the north. I accompanied the captain, not as an officer,

but as a private friend. When we arrived in a high northern latitude I

was viewing the objects around me with the telescope which I

introduced to your notice in my Gibraltar adventures. I thought I saw

two large white bears in violent action upon a body of ice

considerably above the masts, and about half a league distance. I

immediately took my carbine, slung it across my shoulder, and ascended

the ice. When I arrived at the top, the unevenness of the surface made

my approach to those animals troublesome and hazardous beyond

expression: sometimes hideous cavities opposed me, which I was obliged

to spring over; in other parts the surface was as smooth as a mirror,

and I was continually falling: as I approached near enough to reach

them, I found they were only at play. I immediately began to calculate

the value of their skins, for they were each as large as a well-fed

ox: unfortunately, at the very instant I was presenting my carbine my

right foot slipped, I fell upon my back, and the violence of the blow

deprived me totally of my senses for nearly half an hour; however,

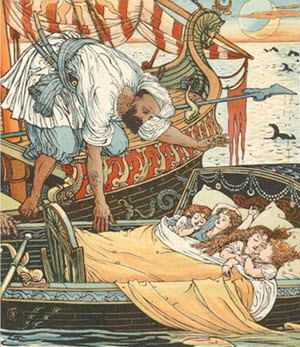

when I recovered, judge of my surprise at finding one of those large

animals I have been just describing had turned me upon my face, and

was just laying hold of the waistband of my breeches, which were then

new and made of leather: he was certainly going to carry me feet

foremost, God knows where, when I took this knife (showing a large

clasp knife) out of my side-pocket, made a chop at one of his hind

feet, and cut off three of his toes; he immediately let me drop and

roared most horribly. I took up my carbine and fired at him as he ran

off; he fell directly. The noise of the piece roused several thousand

of these white bears, who were asleep upon the ice within half a mile

of me; they came immediately to the spot. There was no time to be

lost. A most fortunate thought arrived in my pericranium just at that

instant. I took off the skin and head of the dead bear in half the

time that some people would be in skinning a rabbit, and wrapped

myself in it, placing my own head directly under Bruin's; the whole

herd came round me immediately, and my apprehensions threw me into a

most piteous situation to be sure: however, my scheme turned out a

most admirable one for my own safety. They all came smelling, and

evidently took me for a brother Bruin; I wanted nothing but bulk to

make an excellent counterfeit: however, I saw several cubs amongst

them not much larger than myself. After they had all smelt me, and the

body of their deceased companion, whose skin was now become my

protector, we seemed very sociable, and I found I could mimic all

their actions tolerably well; but at growling, roaring, and hugging

they were quite my masters. I began now to think that I might turn the

general confidence which I had created amongst these animals to my

advantage.

I had heard an old army surgeon say a wound in the spine was instant

death. I now determined to try the experiment, and had again recourse

to my knife, with which I struck the largest in the back of the neck,

near the shoulders, but under great apprehensions, not doubting but

the creature would, if he survived the stab, tear me to pieces.

However, I was remarkably fortunate, for he fell dead at my feet

without making the least noise. I was now resolved to demolish them

every one in the same manner, which I accomplished without the least

difficulty; for although they saw their companions fall, they had no

suspicion of either the cause or the effect. When they all lay dead

before me, I felt myself a second Samson, having slain my thousands.

To make short of the story, I went back to the ship, and borrowed

three parts of the crew to assist me in skinning them, and carrying

the hams on board, which we did in a few hours, and loaded the ship

with them. As to the other parts of the animals, they were thrown into

the sea, though I doubt not but the whole would eat as well as the

legs, were they properly cured.

As soon as we returned I sent some of the hams, in the captain's name,

to the Lords of Admiralty, others to the Lords of the Treasury, some

to the Lord Mayor and Corporation of London, a few to each of the

trading companies, and the remainder to my particular friends, from

all of whom I received warm thanks; but from the city I was honoured

with substantial notice, viz., an invitation to dine at Guildhall

annually on Lord Mayor's day.

The bear-skins I sent to the Empress of Russia, to clothe her majesty

and her court in the winter, for which she wrote me a letter of thanks

with her own hand, and sent it by an ambassador extraordinary,

inviting me to share the honours of her crown; but as I never was

ambitious of royal dignity, I declined her majesty's favour in the

politest terms. The same ambassador had orders to wait and bring my

answer to her majesty /personally/, upon which business he was absent

about three months: her majesty's reply convinced me of the strength

of her affections, and the dignity of her mind; her late indisposition

was entirely owing (as she, kind creature! was pleased to express

herself in a late conversation with the Prince Dolgoroucki) to my

cruelty. What the sex see in me I cannot conceive, but the Empress is

not the only female sovereign who has offered me her hand.

Some people have very illiberally reported that Captain Phipps did not

proceed as far as he might have done upon that expedition. Here it

becomes my duty to acquit him; our ship was in a very proper trim till

I loaded it with such an immense quantity of bear-skins and hams,

after which it would have been madness to have attempted to proceed

further, as we were now scarcely able to combat a brisk gale, much

less those mountains of ice which lay in the higher latitudes.

The captain has since often expressed a dissatisfaction that he had no

share in the honours of that day, which he emphatically called /bear-

skin day/. He has also been very desirous of knowing by what art I

destroyed so many thousands, without fatigue or danger to myself;

indeed, he is so ambitious of dividing the glory with me, that we have

actually quarrelled about it, and we are not now upon speaking terms.

He boldly asserts I had no merit in deceiving the bears, because I was

covered with one of their skins; nay, he declares there is not, in his

opinion, in Europe, so complete a bear naturally as himself among the

human species.

He is now a noble peer, and I am too well acquainted with good manners

to dispute so delicate a point with his lordship.