CHAPTER XX

Mr. Drybones' "Travels to Sicily," which I had read with great

pleasure, induced me to pay a visit to Mount Etna; my voyage to this

place was not attended with any circumstances worth relating. One

morning early, three or four days after my arrival, I set out from a

cottage where I had slept, within six miles of the foot of the

mountain, determined to explore the internal parts, if I perished in

the attempt. After three hours' hard labour I found myself at the top;

it was then, and had been for upwards of three weeks, raging: its

appearance in this state has been so frequently noticed by different

travellers, that I will not tire you with descriptions of objects you

are already acquainted with. I walked round the edge of the crater,

which appeared to be fifty times at least as capacious as the Devil's

Punch-Bowl near Petersfield, on the Portsmouth Road, but not so broad

at the bottom, as in that part it resembles the contracted part of a

funnel more than a punch-bowl. At last, having made up my mind, in I

sprang feet foremost; I soon found myself in a warm berth, and my body

bruised and burnt in various parts by the red-hot cinders, which, by

their violent ascent, opposed my descent: however, my weight soon

brought me to the bottom, where I found myself in the midst of noise

and clamour, mixed with the most horrid imprecations; after recovering

my senses, and feeling a reduction of my pain, I began to look about

me. Guess, gentlemen, my astonishment, when I found myself in the

company of Vulcan and his Cyclops, who had been quarrelling, for the

three weeks before mentioned, about the observation of good order and

due subordination, and which had occasioned such alarms for that space

of time in the world above. However, my arrival restored peace to the

whole society, and Vulcan himself did me the honour of applying

plasters to my wounds, which healed them immediately; he also placed

refreshments before me, particularly nectar, and other rich wines,

such as the gods and goddesses only aspire to. After this repast was

over Vulcan ordered Venus to show me every indulgence which my

situation required. To describe the apartment, and the couch on which

I reposed, is totally impossible, therefore I will not attempt it; let

it suffice to say, it exceeds the power of language to do it justice,

or speak of that kind-hearted goddess in any terms equal to her merit.

Vulcan gave me a very concise account of Mount Etna: he said it was

nothing more than an accumulation of ashes thrown from his forge; that

he was frequently obliged to chastise his people, at whom, in his

passion, he made it a practice to throw red-hot coals at home, which

they often parried with great dexterity, and then threw them up into

the world to place them out of his reach, for they never attempted to

assault him in return by throwing them back again. "Our quarrels,"

added he, "last sometimes three or four months, and these appearances

of coals or cinders in the world are what I find you mortals call

eruptions." Mount Vesuvius, he assured me, was another of his shops,

to which he had a passage three hundred and fifty leagues under the

bed of the sea, where similar quarrels produced similar eruptions. I

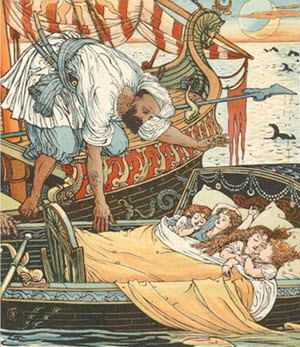

should have continued here as an humble attendant upon Madam Venus,

but some busy tattlers, who delight in mischief, whispered a tale in

Vulcan's ear, which roused in him a fit of jealousy not to be

appeased. Without the least previous notice he took me one morning

under his arm, as I was waiting upon Venus, agreeable to custom, and

carried me to an apartment I had never before seen, in which there

was, to all appearance, /a well/ with a wide mouth: over this he held

me at arm's length, and saying, "/Ungrateful mortal, return to the

world from whence you came/," without giving me the least opportunity

of reply, dropped me in the centre. I found myself descending with an

increasing rapidity, till the horror of my mind deprived me of all

reflection. I suppose I fell into a trance, from which I was suddenly

aroused by plunging into a large body of water illuminated by the rays

of the sun!!

I could, from my infancy, swim well, and play tricks in the water. I

now found myself in paradise, considering the horrors of mind I had

just been released from. After looking about me some time, I could

discover nothing but an expanse of sea, extending beyond the eye in

every direction; I also found it very cold, a different climate from

Master Vulcan's shop. At last I observed at some distance a body of

amazing magnitude, like a huge rock, approaching me; I soon discovered

it to be a piece of floating ice; I swam round it till I found a place

where I could ascend to the top, which I did, but not without some

difficulty. Still I was out of sight of land, and despair returned

with double force; however, before night came on I saw a sail, which

we approached very fast; when it was within a very small distance I

hailed them in German; they answered in Dutch. I then flung myself

into the sea, and they threw out a rope, by which I was taken on

board. I now inquired where we were, and was informed, in the great

Southern Ocean; this opened a discovery which removed all my doubts

and difficulties. It was now evident that I had passed from Mount Etna

through the centre of the earth to the South Seas: this, gentlemen,

was a much shorter cut than going round the world, and which no man

has accomplished, or ever attempted, but myself; however, the next

time I perform it I will be much more particular in my observations.

I took some refreshment, and went to rest. The Dutch are a very rude

sort of people; I related the Etna passage to the officers, exactly as

I have done to you, and some of them, particularly the Captain, seemed

by his grimace and half-sentence to doubt my veracity; however, as he

had kindly taken me on board his vessel, and was then in the very act

of administering to my necessities, I pocketed the affront.

I now in my turn began to inquire where they were bound? To which they

answered, they were in search of new discoveries; "/and if/," said

they, "/your story is true, a new passage is really discovered, and we

shall not return disappointed/." We were now exactly in Captain Cook's

first track, and arrived the next morning in Botany Bay. This place I

would by no means recommend to the English government as a receptacle

for felons, or place of punishment; it should rather be the reward of

merit, nature having most bountifully bestowed her best gifts upon it.

We stayed here but three days; the fourth after our departure a most

dreadful storm arose, which in a few hours destroyed all our sails,

splintered our bowsprit, and brought down our topmast; it fell

directly upon the box that enclosed our compass, which, with the

compass, was broken to pieces. Every one who has been at sea knows the

consequences of such a misfortune: we now were at a loss where to

steer. At length the storm abated, which was followed by a steady,

brisk gale, that carried us at least forty knots an hour for six

months! [we should suppose the Baron has made a little mistake, and

substituted /months/ for /days/] when we began to observe an amazing

change in everything about us: our spirits became light, our noses

were regaled with the most aromatic effluvia imaginable: the sea had

also changed its complexion, and from green became white!! Soon after

these wonderful alterations we saw land, and not at any great distance

an inlet, which we sailed up near sixty leagues, and found it wide and

deep, flowing with milk of the most delicious taste. Here we landed,

and soon found it was an island consisting of one large cheese: we

discovered this by one of the company fainting away as soon as we

landed: this man always had an aversion to cheese; when he recovered,

he desired the cheese to be taken from under his feet: upon

examination we found him perfectly right, for the whole island, as

before observed, was nothing but a cheese of immense magnitude! Upon

this the inhabitants, who are amazingly numerous, principally sustain

themselves, and it grows every night in proportion as it is consumed

in the day. Here seemed to be plenty of vines, with bunches of large

grapes, which, upon being pressed, yielded nothing but milk. We saw

the inhabitants running races upon the surface of the milk: they were

upright, comely figures, nine feet high, have three legs, and but one

arm; upon the whole, their form was graceful, and when they quarrel,

they exercise a straight horn, which grows in adults from the centre

of their foreheads, with great adroitness; they did not sink at all,

but ran and walked upon the surface of the milk, as we do upon a

bowling-green.

Upon this island of cheese grows great plenty of corn, the ears of

which produce loaves of bread, ready made, of a round form like

mushrooms. We discovered, in our rambles over this cheese, seventeen

other rivers of milk, and ten of wine.

After thirty-eight days' journey we arrived on the opposite side to

that on which we landed: here we found some blue mould, as cheese-

eaters call it, from whence spring all kinds of rich fruit; instead of

breeding mites it produced peaches, nectarines, apricots, and a

thousand delicious fruits which we are not acquainted with. In these

trees, which are of an amazing size, were plenty of birds' nests;

amongst others was a king-fisher's of prodigious magnitude; it was at

least twice the circumference of the dome of St. Paul's Church in

London. Upon inspection, this nest was made of huge trees curiously

joined together; there were, let me see (/for I make it a rule always

to speak within compass/), there were upwards of five hundred eggs in

the nest, and each of them was as large as four common hogsheads, or

eight barrels, and we could not only see, but hear the young ones

chirping within. Having, with great fatigue, cut open one of these

eggs, we let out a young one unfeathered, considerably larger than

twenty full-grown vultures. Just as we had given this youngster his

liberty the old kingfisher lighted, and seizing our captain, who had

been active in breaking the egg, in one of her claws, flew with him

above a mile high, and then let him drop into the sea, but not till

she had beaten all his teeth out of his mouth with her wings.

Dutchmen generally swim well: he soon joined us, and we retreated to

our ship. On our return we took a different route, and observed many

strange objects. We shot two wild oxen, each with one horn, also like

the inhabitants, except that it sprouted from between the eyes of

these animals; we were afterwards concerned at having destroyed them,

as we found, by inquiry, they tamed these creatures, and used them as

we do horses, to ride upon and draw their carriages; their flesh, we

were informed, is excellent, but useless where people live upon cheese

and milk. When we had reached within two days' journey of the ship we

observed three men hanging to a tall tree by their heels; upon

inquiring the cause of their punishment, I found they had all been

travellers, and upon their return home had deceived their friends by

describing places they never saw, and relating things that never

happened: this gave me no concern, /as I have ever confined myself to

facts/.

As soon as we arrived at the ship we unmoored, and set sail from this

extraordinary country, when, to our astonishment, all the trees upon

shore, of which there were a great number very tall and large, paid

their respects to us twice, bowing to exact time, and immediately

recovered their former posture, which was quite erect.

By what we could learn of this CHEESE, it was considerably larger than

the continent of all Europe!

After sailing three months we knew not where, being still without

compass, we arrived in a sea which appeared to be almost black: upon

tasting it we found it most excellent wine, and had great difficulty

to keep the sailors from getting drunk with it: however, in a few

hours we found ourselves surrounded by whales and other animals of an

immense magnitude, one of which appeared to be too large for the eye

to form a judgment of: we did not see him till we were close to him.

This monster drew our ship, with all her masts standing, and sails

bent, by suction into his mouth, between his teeth, which were much

larger and taller than the mast of a first-rate man-of-war. After we

had been in his mouth some time he opened it pretty wide, took in an

immense quantity of water, and floated our vessel, which was at least

500 tons burthen, into his stomach; here we lay as quiet as at anchor

in a dead calm. The air, to be sure, was rather warm, and very

offensive. We found anchors, cables, boats, and barges in abundance,

and a considerable number of ships, some laden and some not, which

this creature had swallowed. Everything was transacted by torch-light;

no sun, no moon, no planet, to make observations from. We were all

generally afloat and aground twice a-day; whenever he drank, it became

high water with us; and when he evacuated, we found ourselves aground;

upon a moderate computation, he took in more water at a single draught

than is generally to be found in the Lake of Geneva, though that is

above thirty miles in circumference. On the second day of our

confinement in these regions of darkness, I ventured at low water, as

we called it when the ship was aground, to ramble with the Captain,

and a few of the other officers, with lights in our hands; we met with

people of all nations, to the amount of upwards of ten thousand; they

were going to hold a council how to recover their liberty; some of

them having lived in this animal's stomach several years; there were

several children here who had never seen the world, their mothers

having lain in repeatedly in this warm situation. Just as the chairman

was going to inform us of the business upon which we were assembled,

this plaguy fish, becoming thirsty, drank in his usual manner; the

water poured in with such impetuosity, that we were all obliged to

retreat to our respective ships immediately, or run the risk of being

drowned; some were obliged to swim for it, and with difficulty saved

their lives. In a few hours after we were more fortunate, we met again

just after the monster had evacuated. I was chosen chairman, and the

first thing I did was to propose splicing two main-masts together, and

the next time he opened his mouth to be ready to wedge them in, so as

to prevent his shutting it. It was unanimously approved. One hundred

stout men were chosen upon this service. We had scarcely got our masts

properly prepared when an opportunity offered; the monster opened his

mouth, immediately the top of the mast was placed against the roof,

and the other end pierced his tongue, which effectually prevented him

from shutting his mouth. As soon as everything in his stomach was

afloat, we manned a few boats, who rowed themselves and us into the

world. The daylight, after, as near as we could judge, three months'

confinement in total darkness, cheered our spirits surprisingly. When

we had all taken our leave of this capacious animal, we mustered just

a fleet of ninety-five ships, of all nations, who had been in this

confined situation.

We left the two masts in his mouth, to prevent others being confined

in the same horrid gulf of darkness and filth. Our first object was to

learn what part of the world we were in; this we were for some time at

a loss to ascertain: at last I found, from former observations, that

we were in the Caspian Sea! which washes part of the country of the

Calmuck Tartars. How we came here is was impossible to conceive, as

this sea has no communication with any other. One of the inhabitants

of the Cheese Island, whom I had brought with me, accounted for it

thus:--that the monster in whose stomach we had been so long confined

had carried us here through some subterraneous passage; however, we

pushed to shore, and I was the first who landed. Just as I put my foot

upon the ground a large bear leaped upon me with its fore-paws; I

caught one in each hand, and squeezed him till he cried out most

lustily; however, in this position I held him till I starved him to

death. You may laugh, gentlemen, but this was soon accomplished, as I

prevented him licking his paws. From hence I travelled up to St.

Petersburg a second time: here an old friend gave me a most excellent

pointer, descended from the famous bitch before-mentioned, that

littered while she was hunting a hare. I had the misfortune to have

him shot soon after by a blundering sportsman, who fired at him

instead of a covey of partridges which he had just set. Of this

creature's skin I have had this waistcoat made (showing his

waistcoat), which always leads me involuntarily to game if I walk in

the fields in the proper season, and when I come within shot, /one of

the buttons constantly flies off, and lodges upon the spot where the

sport is/; and as the birds rise, being always primed and cocked, I

never miss them. Here are now but three buttons left. I shall have a

new set sewed on against the shooting season commences.

When a covey of partridges is disturbed in this manner, by the button

falling amongst them, they always rise from the ground in a direct

line before each other. I one day, by forgetting to take my ramrod out

of my gun, shot it straight through a leash, as regularly as if the

cook had spitted them. I had forgot to put in any shot, and the rod

had been made so hot with the powder, that the birds were completely

roasted by the time I reached home.

Since my arrival in England I have accomplished what I had very much

at heart, viz., providing for the inhabitant of the Cheese Island,

whom I had brought with me. My old friend, Sir William Chambers, who

is entirely indebted to me for all his ideas of Chinese gardening, by

a description of which he has gained such high reputation; I say,

gentlemen, in a discourse which I had with this gentlemen, he seemed

much distressed for a contrivance to light the lamps at the new

buildings, Somerset House; the common mode with ladders, he observed,

was both dirty and inconvenient. My native of the Cheese Island popped

into my head; he was only nine feet high when I first brought him from

his own country, but was now increased to ten and a half: I introduced

him to Sir William, and he is appointed to that honourable office. He

is also to carry, under a large cloak, a utensil in each coat pocket,

instead of those four which Sir William has /very properly/ fixed for

private purposes in so conspicuous a situation, the great quadrangle.

He has also obtained from Mr. PITT the situation of messenger to his

Majesty's lords of the bed-chamber, whose principal employment will

/now/ be, divulging the secrets of the Royal household to their

/worthy/ Patron.

SUPPLEMENT

/Extraordinary flight on the back of an eagle, over France to

Gibraltar, South and North America, the Polar Regions, and back to

England, within six-and-thirty hours./

About the beginning of his present Majesty's reign I had some business

with a distant relation who then lived on the Isle of Thanet; it was a

family dispute, and not likely to be finished soon. I made it a

practice during my residence there, the weather being fine, to walk

out every morning. After a few of these excursions I observed an

object upon a great eminence about three miles distant: I extended my

walk to it, and found the ruins of an ancient temple: I approached it

with admiration and astonishment; the traces of grandeur and

magnificence which yet remained were evident proofs of its former

splendour: here I could not help lamenting the ravages and

devastations of time, of which that once noble structure exhibited

such a melancholy proof. I walked round it several times, meditating

on the fleeting and transitory nature of all terrestrial things; on

the eastern end were the remains of a lofty tower, near forty feet

high, overgrown with ivy, the top apparently flat; I surveyed it on

every side very minutely, thinking that if I could gain its summit I

should enjoy the most delightful prospect of the circumjacent country.

Animated with this hope, I resolved, if possible, to gain the summit,

which I at length effected by means of the ivy, though not without

great difficulty and danger; the top I found covered with this

evergreen, except a large chasm in the middle. After I had surveyed

with pleasing wonder the beauties of art and nature that conspired to

enrich the scene, curiosity prompted me to sound the opening in the

middle, in order to ascertain its depth, as I entertained a suspicion

that it might probably communicate with some unexplored subterranean

cavern in the hill; but having no line I was at a loss how to proceed.

After revolving the matter in my thoughts for some time, I resolved to

drop a stone down and listen to the echo: having found one that

answered my purpose I placed myself over the hole, with one foot on

each side, and stooping down to listen, I dropped the stone, which I

had no sooner done than I heard a rustling below, and suddenly a

monstrous eagle put up its head right opposite my face, and rising up

with irresistible force, carried me away seated on its shoulders: I

instantly grasped it round the neck, which was large enough to fill my

arms, and its wings, when extended, were ten yards from one extremity

to the other. As it rose with a regular ascent, my seat was perfectly

easy, and I enjoyed the prospect below with inexpressible pleasure. It

hovered over Margate for some time, was seen by several people, and

many shots were fired at it; one ball hit the heel of my shoe, but did

me no injury. It then directed its course to Dover cliff, where it

alighted, and I thought of dismounting, but was prevented by a sudden

discharge of musketry from a party of marines that were exercising on

the beach; the balls flew about my head, and rattled on the feathers

of the eagle like hail-stones, yet I could not perceive it had

received any injury. It instantly reascended and flew over the sea

towards Calais, but so very high that the Channel seemed to be no

broader than the Thames at London Bridge. In a quarter of an hour I

found myself over a thick wood in France, where the eagle descended

very rapidly, which caused me to slip down to the back part of its

head; but alighting on a large tree, and raising its head, I recovered

my seat as before, but saw no possibility of disengaging myself

without the danger of being killed by the fall; so I determined to sit

fast, thinking it would carry me to the Alps, or some other high

mountain, where I could dismount without any danger. After resting a

few minutes it took wing, flew several times round the wood, and

screamed loud enough to be heard across the English Channel. In a few

minutes one of the same species arose out of the wood, and flew

directly towards us; it surveyed me with evident marks of displeasure,

and came very near me. After flying several times round, they both

directed their course to the south-west. I soon observed that the one

I rode upon could not keep pace with the other, but inclined towards

the earth, on account of my weight; its companion perceiving this,

turned round and placed itself in such a position that the other could

rest its head on its rump; in this manner they proceeded till noon,

when I saw the rock of Gibraltar very distinctly. The day being clear,

notwithstanding my degree of elevation, the earth's surface appeared

just like a map, where land, sea, lakes, rivers, mountains, and the

like were perfectly distinguishable; and having some knowledge of

geography, I was at no loss to determine what part of the globe I was

in.

Whilst I was contemplating this wonderful prospect a dreadful howling

suddenly began all around me, and in a moment I was invested by

thousands of small, black, deformed, frightful looking creatures, who

pressed me on all sides in such a manner that I could neither move

hand or foot: but I had not been in their possession more than ten

minutes when I heard the most delightful music that can possibly be

imagined, which was suddenly changed into a noise the most awful and

tremendous, to which the report of cannon, or the loudest claps of

thunder could bear no more proportion than the gentle zephyrs of the

evening to the most dreadful hurricane; but the shortness of its

duration prevented all those fatal effects which a prolongation of it

would certainly have been attended with.

The music commenced, and I saw a great number of the most beautiful

little creatures seize the other party, and throw them with great

violence into something like a snuff-box, which they shut down, and

one threw it away with incredible velocity; then turning to me, he

said they whom he had secured were a party of devils, who had wandered

from their proper habitation; and that the vehicle in which they were

enclosed would fly with unabating rapidity for ten thousand years,

when it would burst of its own accord, and the devils would recover

their liberty and faculties, as at the present moment. He had no

sooner finished this relation than the music ceased, and they all

disappeared, leaving me in a state of mind bordering on the confines

of despair.

When I had recomposed myself a little, and looking before me with

inexpressible pleasure, I observed that the eagles were preparing to

light on the peak of Teneriffe: they descended on the top of the rock,

but seeing no possible means of escape if I dismounted determined me

to remain where I was. The eagles sat down seemingly fatigued, when

the heat of the sun soon caused them both to fall asleep, nor did I

long resist its fascinating power. In the cool of the evening, when

the sun had retired below the horizon, I was roused from sleep by the

eagle moving under me; and having stretched myself along its back, I

sat up, and reassumed my travelling position, when they both took

wing, and having placed themselves as before, directed their course to

South America. The moon shining bright during the whole night, I had a

fine view of all the islands in those seas.

About the break of day we reached the great continent of America, that

part called Terra Firma, and descended on the top of a very high

mountain. At this time the moon, far distant in the west, and obscured

by dark clouds, but just afforded light sufficient for me to discover

a kind of shrubbery all around, bearing fruit something like cabbages,

which the eagles began to feed on very eagerly. I endeavoured to

discover my situation, but fogs and passing clouds involved me in the

thickest darkness, and what rendered the scene still more shocking was

the tremendous howling of wild beasts, some of which appeared to be

very near: however, I determined to keep my seat, imagining that the

eagle would carry me away if any of them should make a hostile

attempt. When daylight began to appear, I thought of examining the

fruit which I had seen the eagles eat, and as some was hanging which I

could easily come at, I took out my knife and cut a slice; but how

great was my surprise to see that it had all the appearance of roast

beef regularly mixed, both fat and lean! I tasted it, and found it

well flavoured and delicious, then cut several large slices and put in

my pocket, where I found a crust of bread which I had brought from

Margate; took it out, and found three musket-balls that had been

lodged in it on Dover cliff. I extracted them, and cutting a few

slices more, made a hearty meal of bread and cold beef fruit. I then

cut down two of the largest that grew near me, and tying them together

with one of my garters, hung them over the eagle's neck for another

occasion, filling my pockets at the same time. While I was settling

these affairs I observed a large fruit like an inflated bladder, which

I wished to try an experiment upon: and striking my knife into one of

them, a fine pure liquor like Hollands gin rushed out, which the

eagles observing, eagerly drank up from the ground. I cut down the

bladder as fast as I could, and saved about half a pint in the bottom

of it, which I tasted, and could not distinguish it from the best

mountain wine. I drank it all, and found myself greatly refreshed. By

this time the eagles began to stagger against the shrubs. I

endeavoured to keep my seat, but was soon thrown to some distance

among the bushes. In attempting to rise I put my hand upon a large

hedgehog, which happened to lie among the grass upon its back: it

instantly closed round my hand, so that I found it impossible to shake

it off. I struck it several times against the ground without effect;

but while I was thus employed I heard a rustling among the shrubbery,

and looking up, I saw a huge animal within three yards of me; I could

make no defence, but held out both my hands, when it rushed upon me,

and seized that on which the hedgehog was fixed. My hand being soon

relieved, I ran to some distance, where I saw the creature suddenly

drop down and expire with the hedgehog in its throat. When the danger

was past I went to view the eagles, and found them lying on the grass

fast asleep, being intoxicated with the liquor they had drank. Indeed,

I found myself considerably elevated by it, and seeing everything

quiet, I began to search for some more, which I soon found; and having

cut down two large bladders, about a gallon each, I tied them

together, and hung them over the neck of the other eagle, and the two

smaller ones I tied with a cord round my own waist. Having secured a

good stock of provisions, and perceiving the eagles begin to recover,

I again took my seat. In half an hour they arose majestically from the

place, without taking the least notice of their incumbrance. Each

reassumed its former station; and directing their course to the

northward, they crossed the Gulf of Mexico, entered North America, and

steered directly for the Polar regions, which gave me the finest

opportunity of viewing this vast continent that can possibly be

imagined.

Before we entered the frigid zone the cold began to affect me; but

piercing one of my bladders, I took a draught, and found that it could

make no impression on me afterwards. Passing over Hudson's Bay, I saw

several of the Company's ships lying at anchor, and many tribes of

Indians marching with their furs to market.

By this time I was so reconciled to my seat, and become such an expert

rider, that I could sit up and look around me; but in general I lay

along the eagle's neck, grasping it in my arms, with my hands immersed

in its feathers, in order to keep them warm.

In those cold climates I observed that the eagles flew with greater

rapidity, in order, I suppose, to keep their blood in circulation. In

passing Baffin's Bay I saw several large Greenlandmen to the eastward,

and many surprising mountains of ice in those seas.

While I was surveying these wonders of nature it occurred to me that

this was a good opportunity to discover the north-west passage, if any

such thing existed, and not only obtain the reward offered by

government, but the honour of a discovery pregnant with so many

advantages to every European nation. But while my thoughts were

absorbed in this pleasing reverie I was alarmed by the first eagle

striking its head against a solid transparent substance, and in a

moment that which I rode experienced the same fate, and both fell down

seemingly dead.

Here our lives must inevitably have terminated, had not a sense of

danger, and the singularity of my situation, inspired me with a degree

of skill and dexterity which enabled us to fall near two miles

perpendicular with as little inconveniency as if we had been let down

with a rope: for no sooner did I perceive the eagles strike against a

frozen cloud, which is very common near the poles, than (they being

close together) I laid myself along the back of the foremost, and took

hold of its wings to keep them extended, at the same time stretching

out my legs behind to support the wings of the other. This had the

desired effect, and we descended very safe on a mountain of ice, which

I supposed to be about three miles above the level of the sea.

I dismounted, unloaded the eagles, opened one of the bladders, and

administered some of the liquor to each of them, without once

considering that the horrors of destruction seemed to have conspired

against me. The roaring of waves, crashing of ice, and the howling of

bears, conspired to form a scene the most awful and tremendous: but

notwithstanding this, my concern for the recovery of the eagles was so

great, that I was insensible of the danger to which I was exposed.

Having rendered them every assistance in my power, I stood over them

in painful anxiety, fully sensible that it was only by means of them

that I could possibly be delivered from these abodes of despair.

But suddenly a monstrous bear began to roar behind me, with a voice

like thunder. I turned round, and seeing the creature just ready to

devour me, having the bladder of liquor in my hands, through fear I

squeezed it so hard, that it burst, and the liquor flying in the eyes

of the animal, totally deprived it of sight. It instantly turned from

me, ran away in a state of distraction, and soon fell over a precipice

of ice into the sea, where I saw it no more.

The danger being over, I again turned my attention to the eagles, whom

I found in a fair way of recovery, and suspecting that they were faint

for want of victuals, I took one of the beef fruit, cut it into small

slices, and presented them with it, which they devoured with avidity.

Having given them plenty to eat and drink, and disposed of the

remainder of my provision, I took possession of my seat as before.

After composing myself, and adjusting everything in the best manner, I

began to eat and drink very heartily; and through the effects of the

mountain wine, as I called it, was very cheerful, and began to sing a

few verses of a song which I had learned when I was a boy: but the

noise soon alarmed the eagles, who had been asleep, through the

quantity of liquor which they had drank, and they rose seemingly much

terrified. Happily for me, however, when I was feeding them I had

accidentally turned their heads towards the south-east, which course

they pursued with a rapid motion. In a few hours I saw the Western

Isles, and soon after had the inexpressible pleasure of seeing Old

England. I took no notice of the seas or islands over which I passed.

The eagles descended gradually as they drew near the shore, intending,

as I supposed, to alight on one of the Welsh mountains; but when they

came to the distance of about sixty yards two guns were fired at them,

loaded with balls, one of which took place in a bladder of liquor that

hung to my waist; the other entered the breast of the foremost eagle,

who fell to the ground, while that which I rode, having received no

injury, flew away with amazing swiftness.

This circumstance alarmed me exceedingly, and I began to think it was

impossible for me to escape with my life; but recovering a little, I

once more looked down upon the earth, when, to my inexpressible joy, I

saw Margate at a little distance, and the eagle descending on the old

tower whence it had carried me on the morning of the day before. It no

sooner came down than I threw myself off, happy to find that I was

once more restored to the world. The eagle flew away in a few minutes,

and I sat down to compose my fluttering spirits, which I did in a few

hours.

I soon paid a visit to my friends, and related these adventures.

Amazement stood in every countenance; their congratulations on my

returning in safety were repeated with an unaffected degree of

pleasure, and we passed the evening as we are doing now, every person

present paying the highest compliments to my COURAGE and VERACITY.

THE SECOND VOLUME

PREFACE

TO THE SECOND VOLUME

Baron Munchausen has certainly been productive of much benefit to the

literary world; the numbers of egregious travellers have been such,

that they demanded a very Gulliver to surpass them. If Baron de Tott

dauntlessly discharged an enormous piece of artillery, the Baron

Munchausen has done more; he has taken it and swam with it across the

sea. When travellers are solicitous to be the heroes of their own

story, surely they must admit to superiority, and blush at seeing

themselves out-done by the renowned Munchausen: I doubt whether any

one hitherto, Pantagruel, Gargantua, Captain Lemuel, or De Tott, has

been able to out-do our Baron in this species of excellence: and as at

present our curiosity seems much directed to the interior of Africa,

it must be edifying to have the real relation of Munchausen's

adventures there before any further intelligence arrives; for he seems

to adapt himself and his exploits to the spirit of the times, and

recounts what he thinks should be most interesting to his auditors.

I do not say that the Baron, in the following stories, means a satire

on any political matters whatever. No; but if the reader understands

them so, I cannot help it.

If the Baron meets with a parcel of negro ships carrying whites into

slavery to work upon their plantations in a cold climate, should we

therefore imagine that he intends a reflection on the present traffic

in human flesh? And that, if the negroes should do so, it would be

simple justice, as retaliation is the law of God! If we were to think

this a reflection on any present commercial or political matter, we

should be tempted to imagine, perhaps, some political ideas conveyed

in every page, in every sentence of the whole. Whether such things are

or are not the intentions of the Baron the reader must judge.

We have had not only wonderful travellers in this vile world, but

splenetic travellers, and of these not a few, and also conspicuous

enough. It is a pity, therefore, that the Baron has not endeavoured to

surpass them also in this species of story-telling. Who is it can read

the travels of Smellfungus, as Sterne calls him, without admiration?

To think that a person from the North of Scotland should travel

through some of the finest countries in Europe, and find fault with

everything he meets--nothing to please him! And therefore, methinks,

the Tour to the Hebrides is more excusable, and also perhaps Mr.

Twiss's Tour in Ireland. Dr. Johnson, bred in the luxuriance of

London, with more reason should become cross and splenetic in the

bleak and dreary regions of the Hebrides.

The Baron, in the following work, seems to be sometimes philosophical;

his account of the language of the interior of Africa, and its analogy

with that of the inhabitants of the moon, show him to be profoundly

versed in the etymological antiquities of nations, and throw new light

upon the abstruse history of the ancient Scythians, and the

Collectanea.

His endeavour to abolish the custom of eating live flesh in the

interior of Africa, as described in Bruce's Travels, is truly humane.

But far be it from me to suppose, that by Gog and Magog and the Lord

Mayor's show he means a satire upon any person or body of persons

whatever: or, by a tedious litigated trial of blind judges and dumb

matrons following a wild goose chase all round the world, he should

glance at any trial whatever.

Nevertheless, I must allow that it was extremely presumptuous in

Munchausen to tell half the sovereigns of the world that they were

wrong, and advise them what they ought to do; and that instead of

ordering millions of their subjects to massacre one another, it would

be more to their interest to employ their forces in concert for the

general good; as if he knew better than the Empress of Russia, the

Grand Vizier, Prince Potemkin, or any other butcher in the world. But

that he should be a royal Aristocrat, and take the part of the injured

Queen of France in the present political drama, I am not at all

surprised; but I suppose his mind was fired by reading the pamphlet

written by Mr. Burke.