CHAPTER XXIV

I perceived with grief and consternation the miscarriage of all my

apparatus; yet I was not absolutely dejected: a great mind is never

known but in adversity. With permission of the Dutch governor the

chariot was properly laid up in a great storehouse, erected at the

water's edge, and the bulls received every refreshment possible after

so terrible a voyage. Well, you may be sure they deserved it, and

therefore every attendance was engaged for them, until I should

return.

As it was not possible to do anything more I took my passage in a

homeward-bound Indiaman, to return to London, and lay the matter

before the Privy Council.

We met with nothing particular until we arrived upon the coast of

Guinea, where, to our utter astonishment, we perceived a great hill,

seemingly of glass, advancing against us in the open sea; the rays of

the sun were reflected upon it with such splendour, that it was

extremely difficult to gaze at the phenomenon. I immediately knew it

to be an island of ice, and though in so very warm a latitude,

determined to make all possible sail from such horrible danger. We did

so, but all in vain, for about eleven o'clock at night, blowing a very

hard gale, and exceedingly dark, we struck upon the island. Nothing

could equal the distraction, the shrieks, and despair of the whole

crew, until I, knowing there was not a moment to be lost, cheered up

their spirits, and bade them not despond, but do as I should request

them. In a few minutes the vessel was half full of water, and the

enormous castle of ice that seemed to hem us in on every side, in some

places falling in hideous fragments upon the deck, killed one half of

the crew; upon which, getting upon the summit of the mast, I contrived

to make it fast to a great promontory of the ice, and calling to the

remainder of the crew to follow me, we all escaped from the wreck, and

got upon the summit of the island.

The rising sun soon gave us a dreadful prospect of our situation, and

the loss, or rather iceification, of the vessel; for being closed in

on every side with castles of ice during the night, she was absolutely

frozen over and buried in such a manner that we could behold her under

our feet, even in the central solidity of the island. Having debated

what was best to be done, we immediately cut down through the ice, and

got up some of the cables of the vessel, and the boats, which, making

fast to the island, we towed it with all our might, determined to

bring home island and all, or perish in the attempt. On the summit of

the island we placed what oakum and dregs of every kind of matter we

could get from the vessel, which, in the space of a very few hours, on

account of the liquefying of the ice, and the warmth of the sun, were

transformed into a very fine manure; and as I had some seeds of exotic

vegetables in my pocket, we shortly had a sufficiency of fruits and

roots growing upon the island to supply the whole crew, especially the

bread-fruit tree, a few plants of which had been in the vessel; and

another tree, which bore plum-puddings so very hot, and with such

exquisite proportion of sugar, fruit, &c., that we all acknowledged it

was not possible to taste anything of the kind more delicious in

England: in short, though the scurvy had made such dreadful progress

among the crew before our striking upon the ice, the supply of

vegetables, and especially the bread-fruit and pudding-fruit, put an

almost immediate stop to the distemper.

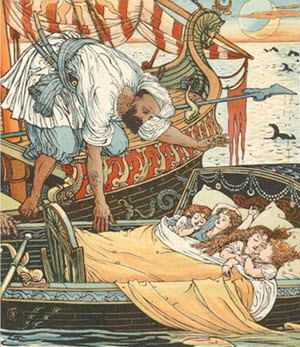

We had not proceeded thus many weeks, advancing with incredible

fatigue by continual towing, when we fell in with a fleet of Negro-

men, as they call them. These wretches, I must inform you, my dear

friends, had found means to make prizes of those vessels from some

Europeans upon the coast of Guinea, and tasting the sweets of luxury,

had formed colonies in several new discovered islands near the South

Pole, where they had a variety of plantations of such matters as would

only grow in the coldest climates. As the black inhabitants of Guinea

were unsuited to the climate and excessive cold of the country, they

formed the diabolical project of getting Christian slaves to work for

them. For this purpose they sent vessels every year to the coast of

Scotland, the northern parts of Ireland, and Wales, and were even

sometimes seen off the coast of Cornwall. And having purchased, or

entrapped by fraud or violence, a great number of men, women, and

children, they proceeded with their cargoes of human flesh to the

other end of the world, and sold them to their planters, where they

were flogged into obedience, and made to work like horses all the rest

of their lives.

My blood ran cold at the idea, while every one on the island also

expressed his horror that such an iniquitous traffic should be

suffered to exist. But, except by open violence, it was found

impossible to destroy the trade, on account of a barbarous prejudice,

entertained of late by the negroes, that the white people have no

souls! However, we were determined to attack them, and steering down

our island upon them, soon overwhelmed them: we saved as many of the

white people as possible, but pushed all the blacks into the water

again. The poor creatures we saved from slavery were so overjoyed,

that they wept aloud through gratitude, and we experienced every

delightful sensation to think what happiness we should shower upon

their parents, their brothers and sisters and children, by bringing

them home safe, redeemed from slavery, to the bosom of their native

country.

Having happily arrived in England, I immediately laid a statement of

my voyage, &c., before the Privy Council, and entreated an immediate

assistance to travel into Africa, and, if possible, refit my former

machine, and take it along with the rest. Everything was instantly

granted to my satisfaction, and I received orders to get myself ready

for departure as soon as possible.

As the Emperor of China had sent a most curious animal as a present to

Europe, which was kept in the Tower, and it being of an enormous

stature, and capable of performing the voyage with /éclat/, she was

ordered to attend me. She was called Sphinx, and was one of the most

tremendous though magnificent figures I ever beheld. She was harnessed

with superb trappings to a large flat-bottomed boat, in which was

placed an edifice of wood, exactly resembling Westminster Hall. Two

balloons were placed over it, tackled by a number of ropes to the

boat, to keep up a proper equilibrium, and prevent it from

overturning, or filling, from the prodigious weight of the fabric.

The interior of the edifice was decorated with seats, in the form of

an amphitheatre, and crammed as full as it could hold with ladies and

lords, as a council and retinue for your humble servant. Nearly in the

centre was a seat elegantly decorated for myself, and on either side

of me were placed the famous Gog and Magog in all their pomp.

The Lord Viscount Gosamer being our postillion, we floated gallantly

down the river, the noble Sphinx gambolling like the huge leviathan,

and towing after her the boat and balloons.

Thus we advanced, sailing gently, into the open sea; being calm

weather, we could scarcely feel the motion of the vehicle, and passed

our time in grand debate upon the glorious intention of our voyage,

and the discoveries that would result.

"I am of opinion," said my noble friend, Hilaro Frosticos, "that

Africa was originally inhabited for the greater part, or, I may say,

subjugated by lions which, next to man, seem to be the most dreaded of

all mortal tyrants. The country in general--at least, what we have

been hitherto able to discover, seems rather inimical to human life;

the intolerable dryness of the place, the burning sands that overwhelm

whole armies and cities in general ruin, and the hideous life many

roving hordes are compelled to lead, incline me to think, that if ever

we form any great settlements therein, it will become the grave of our

countrymen. Yet it is nearer to us than the East Indies, and I cannot

but imagine, that in many places every production of China, and of the

East and West Indies, would flourish, if properly attended to. And as

the country is so prodigiously extensive and unknown, what a source of

discovery must not it contain! In fact, we know less about the

interior of Africa than we do of the moon; for in this latter we

measure the very prominences, and observe the varieties and

inequalities of the surface through our glasses--

"Forests and mountains on her spotted orb.

"But we see nothing in the interior of Africa, but what some compilers

of maps or geographers are fanciful enough to imagine. What a happy

event, therefore, should we not expect from a voyage of discovery and

colonisation undertaken in so magnificent a style as the present! what

a pride--what an acquisition to philosophy!"