CHAPTER XXV

The brave Count Gosamer, with a pair of hell-fire spurs on, riding

upon Sphinx, directed the whole retinue towards the Madeiras. But the

Count had no small share of an amiable vanity, and perceiving great

multitudes of people, Gascons, &c., assembled upon the French coast,

he could not refrain from showing some singular capers, such as they

had never seen before: but especially when he observed all the members

of the National Assembly extend themselves along the shore, as a piece

of French politeness, to honour this expedition, with Rousseau,

Voltaire, and Beelzebub at their head; he set spurs to Sphinx, and at

the same time cut and cracked away as hard as he could, holding in the

reins with all his might, striving to make the creature plunge and

show some uncommon diversion. But sulky and ill-tempered was Sphinx at

the time: she plunged indeed--such a devil of a plunge, that she

dashed him in one jerk over her head, and he fell precipitately into

the water before her. It was in the Bay of Biscay, all the world knows

a very boisterous sea, and Sphinx, fearing he would be drowned, never

turned to the left or the right out of her way, but advancing furious,

just stooped her head a little, and supped the poor count off the

water, into her mouth, together with the quantity of two or three tuns

of water, which she must have taken in along with him, but which were,

to such an enormous creature as Sphinx, nothing more than a spoonful

would be to any of you or me. She swallowed him, but when she had got

him in her stomach, his long spurs so scratched and tickled her, that

they produced the effect of an emetic. No sooner was he in, but out he

was squirted with the most horrible impetuosity, like a ball or a

shell from the calibre of a mortar. Sphinx was at this time quite sea-

sick, and the unfortunate count was driven forth like a sky-rocket,

and landed upon the peak of Teneriffe, plunged over head and ears in

the snow--/requiescat in pace!/

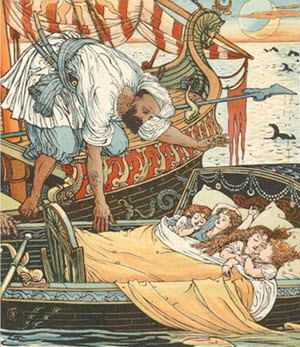

I perceived all this mischief from my seat in the ark, but was in such

a convulsion of laughter that I could not utter an intelligible word.

And now Sphinx, deprived of her postillion, went on in a zigzag

direction, and gambolled away after a most dreadful manner. And thus

had everything gone to wreck, had I not given instant orders to Gog

and Magog to sally forth. They plunged into the water, and swimming on

each side, got at length right before the animal, and then seized the

reins. Thus they continued swimming on each side, like tritons,

holding the muzzle of Sphinx, while I, sallying forth astride upon the

creature's back, steered forward on our voyage to the Cape of Good

Hope.

Arriving at the Cape, I immediately gave orders to repair my former

chariot and machines, which were very expeditiously performed by the

excellent artists I had brought with me from Europe. And now

everything being refitted, we launched forth upon the water: perhaps

there never was anything seen more glorious or more august. 'Twas

magnificent to behold Sphinx make her obeisance on the water, and the

crickets chirp upon the bulls in return of the salute; while Gog and

Magog, advancing, took the reins of the great John Mowmowsky, and

leading towards us chariot and all, instantly disposed of them to the

forepart of the ark by hooks and eyes, and tackled Sphinx before all

the bulls. Thus the whole had a most tremendous and triumphal

appearance. In front floated forwards the mighty Sphinx, with Gog and

Magog on each side; next followed in order the bulls with crickets

upon their heads; and then advanced the chariot of Queen Mab,

containing the curious seat and orrery of heaven; after which appeared

the boat and ark of council, overtopped with two balloons, which gave

an air of greater lightness and elegance to the whole. I placed in the

galleries under the balloons, and on the backs of the bulls, a number

of excellent vocal performers, with martial music of clarionets and

trumpets. They sung the "Watery Dangers," and the "Pomp of Deep

Cerulean!" The sun shone glorious on the water while the procession

advanced toward the land, under five hundred arches of ice,

illuminated with coloured lights, and adorned in the most grotesque

and fanciful style with sea-weed, elegant festoons, and shells of

every kind; while a thousand water-spouts danced eternally before and

after us, attracting the water from the sea in a kind of cone, and

suddenly uniting with the most fantastical thunder and lightning.

Having landed our whole retinue, we immediately began to proceed

toward the heart of Africa, but first thought it expedient to place a

number of wheels under the ark for its greater facility of advancing.

We journeyed nearly due north for several days, and met with nothing

remarkable except the astonishment of the savage natives to behold our

equipage.

The Dutch Government at the Cape, to do them justice, gave us every

possible assistance for the expedition. I presume they had received

instruction on that head from their High Mightinesses in Holland.

However, they presented us with a specimen of some of the most

excellent of their Cape wine, and showed us every politeness in their

power. As to the face of the country, as we advanced, it appeared in

many places capable of every cultivation, and of abundant fertility.

The natives and Hottentots of this part of Africa have been frequently

described by travellers, and therefore it is not necessary to say any

more about them. But in the more interior parts of Africa the

appearance, manners, and genius of the people are totally different.

We directed our course by the compass and the stars, getting every day

prodigious quantities of game in the woods, and at night encamping

within a proper enclosure for fear of the wild beasts. One whole day

in particular we heard on every side, among the hills, the horrible

roaring of lions, resounding from rock to rock like broken thunder. It

seemed as if there was a general rendezvous of all these savage

animals to fall upon our party. That whole day we advanced with

caution, our hunters scarcely venturing beyond pistol shot from the

caravan for fear of dissolution. At night we encamped as usual, and

threw up a circular entrenchment round our tents. We had scarce

retired to repose when we found ourselves serenaded by at least one

thousand lions, approaching equally on every side, and within a

hundred paces. Our cattle showed the most horrible symptoms of fear,

all trembling, and in cold perspiration. I directly ordered the whole

company to stand to their arms, and not to make any noise by firing

till I should command them. I then took a large quantity of tar, which

I had brought with our caravan for that purpose, and strewed it in a

continued stream round the encampment, within which circle of tar I

immediately placed another train or circle of gunpowder, and having

taken this precaution, I anxiously waited the lions' approach. These

dreadful animals, knowing, I presume, the force of our troop, advanced

very slowly, and with caution, approaching on every side of us with an

equal pace, and growling in hideous concert, so as to resemble an

earthquake, or some similar convulsion of the world. When they had at

length advanced and steeped all their paws in the tar, they put their

noses to it, smelling it as if it were blood, and daubed their great

bushy hair and whiskers with it equal to their paws. At that very

instant, when, in concert, they were to give the mortal dart upon us,

I discharged a pistol at the train of gunpowder, which instantly

exploded on every side, made all the lions recoil in general uproar,

and take to flight with the utmost precipitation. In an instant we

could behold them scattered through the woods at some distance,

roaring in agony, and moving about like so many Will-o'-the-Wisps,

their paws and faces all on fire from the tar and the gun-powder. I

then ordered a general pursuit: we followed them on every side through

the woods, their own light serving as our guide, until, before the

rising of the sun, we followed into their fastnesses and shot or

otherwise destroyed every one of them, and during the whole of our

journey after we never heard the roaring of a lion, nor did any wild

beast presume to make another attack upon our party, which shows the

excellence of immediate presence of mind, and the terror inspired into

the savage enemies by a proper and well-timed proceeding.

We at length arrived on the confines of an immeasurable desert--an

immense plain, extending on every side of us like an ocean. Not a

tree, nor a shrub, nor a blade of grass was to be seen, but all

appeared an extreme fine sand, mixed with gold-dust and little

sparkling pearls.

The gold-dust and pearls appeared to us of little value, because we

could have no expectation of returning to England for a considerable

time. We observed, at a great distance, something like a smoke arising

just over the verge of the horizon, and looking with our telescopes we

perceived it to be a whirlwind tearing up the sand and tossing it

about in the heavens with frightful impetuosity. I immediately ordered

my company to erect a mound around us of a great size, which we did

with astonishing labour and perseverance, and then roofed it over with

certain planks and timber, which we had with us for the purpose. Our

labour was scarcely finished when the sand came rolling in like the

waves of the sea; 'twas a storm and river of sand united. It continued

to advance in the same direction, without intermission, for three

days, and completely covered over the mound we had erected, and buried

us all within. The intense heat of the place was intolerable; but

guessing, by the cessation of the noise, that the storm was passed, we

set about digging a passage to the light of day again, which we

effected in a very short time, and ascending, perceived that the whole

had been so completely covered with the sand, that there appeared no

hills, but one continued plain, with inequalities or ridges on it like

the waves of the sea. We soon extricated our vehicle and retinue from

the burning sands, but not without great danger, as the heat was very

violent, and began to proceed on our voyage. Storms of sand of a

similar nature several times attacked us, but by using the same

precautions we preserved ourselves repeatedly from destruction. Having

travelled more than nine thousand miles over this inhospitable plain,

exposed to the perpendicular rays of a burning sun, without ever

meeting a rivulet, or a shower from heaven to refresh us, we at length

became almost desperate, when, to our inexpressible joy, we beheld

some mountains at a great distance, and on our nearer approach

observed them covered with a carpet of verdure and groves and woods.

Nothing could appear more romantic or beautiful than the rocks and

precipices intermingled with flowers and shrubs of every kind, and

palm-trees of such a prodigious size as to surpass anything ever seen

in Europe. Fruits of all kinds appeared growing wild in the utmost

abundance, and antelopes and sheep and buffaloes wandered about the

groves and valleys in profusion. The trees resounded with the melody

of birds, and everything displayed a general scene of rural happiness

and joy.