Home > Secret Rooms and Hiding Places > >

Chapter: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] [9] [10] [11] [12] [13] [14] [15] [16] [17]

ENTRANCE TO HIDING-PLACE, PARHAM HALL

UNDERGROUND PASSAGES

Numerous old houses possess secret doors, passages, and staircases—Franks, in Kent; Eshe Hall, Durham; Binns House, Scotland; Dannoty Hall, and Whatton Abbey, Yorkshire; are examples. The last of these has a narrow flight of steps leading down to the moat, as at Baddesley Clinton. The old house Marks, near Romford, pulled down in 1808 after many years of neglect and decay—as well as the ancient seat of the Tichbournes in Hampshire, pulled down in 1803—and the west side of Holme Hall, Lancashire, demolished in the last century, proved to have been riddled with hollow walls. Secret doors and panels are still pointed out at Bramshill, Hants (in the long gallery and billiard-room); the oak room, Bochym House, Cornwall; the King's bedchamber, Ford Castle, Northumberland; the plotting-parlour of the White Hart Hotel, Hull; Low Hall, Yeadon, Yorkshire; Sawston; the Queen's chamber at Kimbolton Castle, Huntingdonshire, etc., etc.

A concealed door exists on the left-hand side of the fireplace of the gilt room of Holland House, Kensington, associated by tradition with the ghost of the first Lord Holland. Upon the authority of the Princess Lichtenstein, it appears there is, close by, a blood-stain which nothing can efface! It is to be hoped no enterprising person may be induced to try his skill here with the success that attended a similar attempt at Holyrood, as recorded by Scott![1]

[Footnote 1: Vide Introduction to The Fair Maid of Perth]

In the King's writing-closet at Hampton Court may be seen the "secret door" by which William III. left the palace when he wished to go out unobserved; but this is more of a private exit than a secret one.

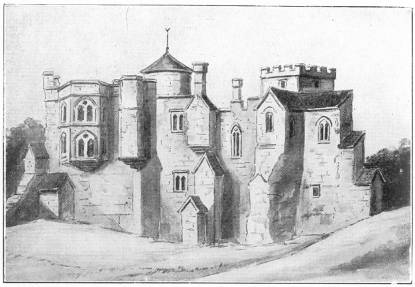

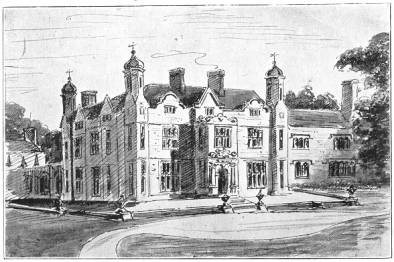

WOODSTOCK PALACE, OXFORDSHIRE (FROM AN OLD PRINT)

MARKYATE CELL, HERTFORDSHIRE

The old Château du Puits, Guernsey, has a hiding-hole placed between two walls which form an acute angle; the one constituting part of the masonry of an inner courtyard, the other a wall on the eastern side of the main structure. The space between could be reached through the floor of an upper room.

Cussans, in his History of Hertfordshire, gives a curious account of the discovery of an iron door up the kitchen chimney of the old house Markyate Cell, near Dunstable. A short flight of steps led from it to another door of stout oak, which opened by a secret spring, and led to an unknown chamber on the ground level. Local tradition says this was the favourite haunt of a certain "wicked Lady Ferrers," who, disguised in male attire, robbed travellers upon the highway, and being wounded in one of these exploits, was discovered lying dead outside the walls of the house; and the malignant nature of this lady's spectre is said to have had so firm a hold upon the villagers that no local labourer could be induced to work upon that particular part of the building.

Beare Park, near Middleham, Yorkshire, had a hiding-hole entered from the kitchen chimney, as had also the Rookery Farm, near Cromer; West Coker Manor House; and The Chantry, at Ilminster, both in Somerset. At the last named, in another hiding-place in the room above, a bracket or credence-table was found, which is still preserved.

Many weird stories are told about Bovey House, South Devon, situated near the once notorious smuggling villages of Beer and Branscombe. Upon removing some leads of the roof a secret room was found, furnished with a chair and table. The well here is remarkable, and similar to that at Carisbrooke, with the exception that two people take the place of the donkey! Thirty feet below the ground level there is said to have been a hiding-place—a large cavity cut in the solid rock. Many years ago a skeleton of a man was found at the bottom. Such dramatic material should suggest to some sensational novelist a tragic story, as the well and lime-walk at Ingatestone is said to have suggested Lady Audley's Secret.

A hiding-place something after the same style existed in the now demolished manor house of Besils Leigh, Berks. Down the shaft of a chimney a cavity was scooped out of the brickwork, to which a refugee had to be lowered by a rope. One of the towers of the west gate of Bodiam Castle contains a narrow square well in the wall leading to the ground level, and, as the guide was wont to remark, "how much farther the Lord only knows"! This sort of thing may also be seen at Mancetter Manor, Warwickshire, and Ightham Moat, Kent, both approached by a staircase.

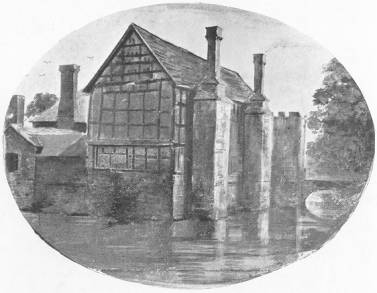

A communication formerly ran from a secret chamber in the oak-panelled dining-room of Birtsmorton Court, Worcestershire, to a passage beneath the moat that surrounds the structure, and thence to an exit on the other side of the water. During the Wars of the Roses Sir John Oldcastle is said to have been concealed behind the secret panel; but now the romance is somewhat marred, for modern vandalism has converted the cupboard into a repository for provisions. The same indignity has taken place at that splendid old timber house in Cheshire, Moreton Hall, where a secret room, provided with a sleeping-compartment, situated over the kitchen, has been modernised into a repository for the storing of cheeses. From the hiding-place the moat could formerly be reached, down a narrow shaft in the wall.

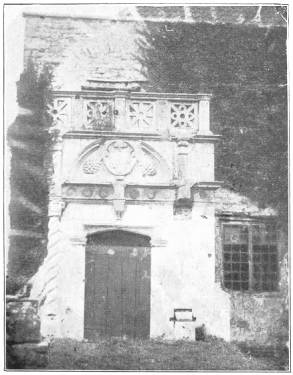

Chelvey Court, near Bristol, contained two hiding-places; one, at the top of the house, was formerly entered through a panel, the other (a narrow apartment having a little window, and an iron candle-holder projecting from the wall) through the floor of a cupboard.[1] Both the panel and the trap-door are now done away with, and the tradition of the existence of the secret rooms almost forgotten, though not long since we received a letter from an antiquarian who had seen them thirty years before, and who was actually entertaining the idea of making practical investigations with the aid of a carpenter or mason, to which, as suggested, we were to be a party; the idea, however, was never carried out.

[Footnote 1: See Notes and Queries, September, 1855.]

BIRTSMORTON COURT, WORCESTERSHIRE

PORCH, CHELVEY COURT, SOMERSETSHIRE

Granchester Manor House, Cambridgeshire, until recently possessed three places of concealment. Madingley Hall, in the same neighbourhood, has two, one of them entered from a bedroom on the first floor, has a space in the thickness of the wall high enough for a man to stand upright in it. The manor house of Woodcote, Hants, also possessed two, which were each capable of holding from fifteen to twenty men, but these repositories are now opened out into passages. One was situated behind a stack of chimneys, and contained an inner hiding-place. The "priests' quarters" in connection with the hiding-places are still to be seen.

.Harborough Hall, Worcestershire, has two "priests' holes," one in the wall of the dining-room, the other behind a chimney in an upper room.

The old mansion of the Brudenells, in Northamptonshire, Deene Park, has a large secret chamber at the back of the fireplace in the great hall, sufficiently capacious to hold a score of people. Here also a hidden door in the panelling leads towards a subterranean passage running in the direction of the ruinous hall of Kirby, a mile and a half distant. In a like manner a passage extended from the great hall of Warleigh, an Elizabethan house near Plymouth, to an outlet in a cliff some sixty yards away, at whose base the tidal river flows.

Speke Hall, Lancashire (perhaps the finest specimen extant of the wood-and-plaster style of architecture nicknamed "Magpie "), formerly possessed a long underground communication extending from the house to the shore of the river Mersey; a member of the Norreys family concealed a priest named Richard Brittain here in the year 1586, who, by this means, effected his escape by boat.

UNDERGROUND PASSAGES

The famous secret passage of Nottingham Castle, by which the young King Edward III. and his loyal associates gained access to the fortress and captured the murderous regent and usurper Mortimer, Earl of March, is known to this day as "Mortimer's Hole." It runs up through the perpendicular rock upon which the castle stands, on the south-east side from a place called Brewhouse yard, and has an exit in what was originally the courtyard of the building. The Earl was seized in the midst of his adherents and retainers on the night of October 19th, 1330, and after a skirmish, notwithstanding the prayers and entreaties of his paramour Queen Isabella, he was bound and carried away through the passage in the rock, and shortly afterwards met his well-deserved death on the gallows at Smithfield.

But what ancient castle, monastery, or hall has not its traditional subterranean passage? Certainly the majority are mythical; still, there are some well authenticated. Burnham Abbey, Buckinghamshire, for example, or Tenterden Hall, Hendon, had passages which have been traced for over fifty yards; and one at Vale Royal, Nottinghamshire, has been explored for nearly a mile. In the older portions in both of the great wards of Windsor Castle arched passages thread their way below the basement, through the chalk, and penetrate to some depth below the site of the castle ditch at the base of the walls.[1] In the neighbourhood of Ripon subterranean passages have been found from time to time—tunnels of finely moulded masonry supposed to have been connected at one time with Fountains Abbey.

[Footnote 1: See Marquis of Lorne's (Duke of Argyll) Governor's Guide to Windsor.]

A passage running from Arundel Castle in the direction of Amberley has also been traced for some considerable distance, and a man and a dog have been lost in following its windings, so the entrance is now stopped up. About three years ago a long underground way was discovered at Margate, reaching from the vicinity of Trinity Church to the smugglers' caves in the cliffs; also at Port Leven, near Helston, a long subterranean tunnel was discovered leading to the coast, no doubt very useful in the good old smuggling days. At Sunbury Park, Middlesex, was found a long vaulted passage some five feet high and running a long way under the grounds. Numerous other examples could be stated, among them at St. Radigund's Abbey, near Dover; Liddington Manor House, Wilts; the Bury, Rickmansworth; "Sir Harry Vane's House," Hampstead, etc., etc.