Home > Secret Rooms and Hiding Places > >

Chapter: [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] [9] [10] [11] [12] [13] [14] [15] [16] [17]

UFTON COURT GARDEN TERRACE, BERKSHIRE

THE GUNPOWDER PLOT CONSPIRATORS

Hidden Rooms

.

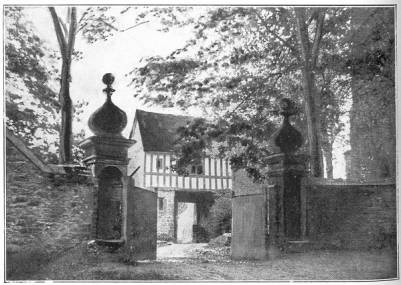

Lord Vaux of Harrowden, Sir William Catesby of Ashby St. Ledgers, and Sir Thomas Tresham of Rushton Hall (all in Northamptonshire) were upon more than one occasion arraigned before the Court of the Star Chamber for harbouring Jesuits. The old mansions Ashby St. Ledgers and Rushton fortunately still remain intact and preserve many traditions of Romanist plots. Sir William Catesby's son Robert, the chief conspirator, is said to have held secret meetings in the curious oak-panelled room over the gate-house of the former, which goes by the name of "the Plot Room." Once upon a time it was provided with a secret means of escape. At Rushton Hall a hiding-place was discovered in 1832 behind a lintel over a doorway; it was full of bundles of manuscripts, prohibited books, and incriminating correspondence of the conspirator Tresham. Another place of concealment was situated in the chimney of the great hall and in this Father Oldcorn was hidden for a time. Gayhurst, or Gothurst, in Buckinghamshire, the seat of Sir Everard Digby, also remains intact, one of the finest late Tudor buildings in the country; unfortunately, however, only recently a remarkable "priest's hole" that was here has been destroyed in consequence of modern improvements. It was a double hiding-place, one situated beneath the other; the lower one being so arranged as to receive light and air from the bottom portion of a large mullioned window—a most ingenious device. A secret passage in the hall had communication with it, and entrance was obtained through part of the flooring of an apartment, the movable part of the boards revolving upon pivots and sufficiently solid to vanquish any suspicion as to a hollow space beneath.

ASHBY ST. LEDGERS, NORTHAMPTONSHIRE

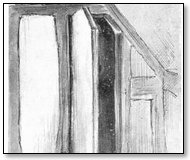

THE PLOT ROOM, ASHBY ST. LEGERS

As may be supposed, tradition says that at the time of Digby's arrest he was dragged forth from this hole, but history shows that he was taken prisoner at Holbeach House (where, it will be remembered, the conspirators Catesby and Percy were shot), and led to execution. For a time Digby sought security at Coughton Court, the seat of the Throckmortons, in Warwickshire. The house of this old Roman Catholic family, of course, had its hiding-holes, one of which remains to this day. Holbeach as well as Hagley Hall, the homes of the Litteltons, have been rebuilt. The latter was pulled down in the middle of the eighteenth century. Here it was that Stephen Littleton and Robert Winter were captured through the treachery of the cook. Grant's house, Norbrook, in Warwickshire, has also given way to a modern one.

Ambrose Rookwood's seat, Coldham Hall, near Bury St. Edmunds, exists and retains its secret chapel and hiding-places. There are three of the latter; one of them, now a small withdrawing-room, is entered from the oak wainscoted hall. When the house was in the market a few years ago, the "priests' holes" duly figured in the advertisements with the rest of the apartments and offices. It read a little odd, this juxtaposition of modern conveniences with what is essentially romantic, and we simply mention the fact to show that the auctioneer is well aware of the monetary value of such things.

At the time of the Gunpowder Conspiracy Rookwood rented Clopton Hall, near Stratford-on-Avon. This house also has its little chapel in the roof with adjacent "priests' holes," but many alterations have taken place from time to time. Who does not remember William Howitt's delightful description—or, to be correct, the description of a lady correspondent—of the old mansion before these restorations. "There was the old Catholic chapel," she wrote, "with a chaplain's room which had been walled up and forgotten till within the last few years. I went in on my hands and knees, for the entrance was very low. I recollect little in the chapel; but in the chaplain's room were old and I should think rare editions of many books, mostly folios. A large yellow paper copy of Dryden's All for Love, or the World Well Lost, date 1686, caught my eye, and is the only one I particularly remember."[1]

[Footnote 1: Howitt's Visits to Remarkable Places.]

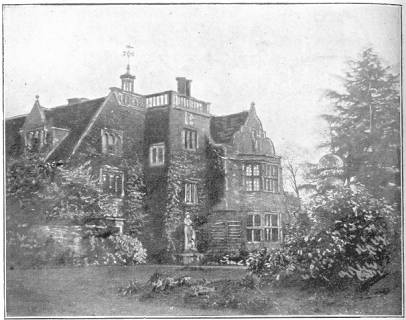

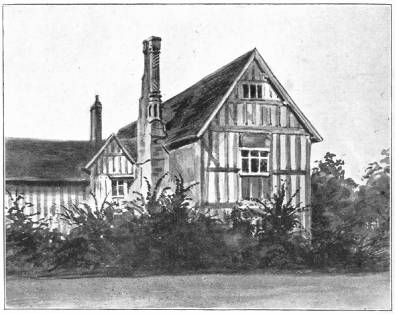

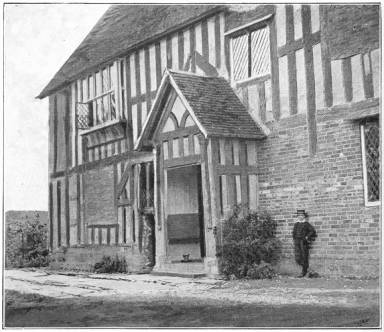

Huddington Court, the picturesque old home of the Winters (of whom Robert and Thomas lost their lives for their share in the Plot), stands a few miles from Droitwich. A considerable quantity of arms and ammunition were stored in the hiding-places here in 1605 in readiness for general rising.

HUDDINGTON COURT, WORCESTERSHIRE

ENTRANCE PORCH, HUDDINGTON COURT

Two other houses may be mentioned in connection with the memorable Plot—houses that were rented by the conspirators as convenient places of rendezvous an account of their hiding-places and masked exits for escape. One of them stood in the vicinity of the Strand, in the fields behind St. Clement's Inn. Father Gerard had taken it some time previous to the discovery of the Plot, and with Owen's aid some very secure hiding-places were arranged. This he had done with two or three other London residences, so that he and his brother priests might use them upon hazardous occasions; and to one of these he owed his life when the hue and cry after him was at its highest pitch. By removing from one to the other they avoided detection, though they had many narrow escapes. One priest was celebrating Mass when the Lord Mayor and constables suddenly burst in. But the surprise party was disappointed: nothing could be detected beyond the smoke of the extinguished candles; and in addition to the hole where the fugitive crouched there were two other secret chambers, neither of which was discovered. On another occasion a priest was left shut up in a wall; his friends were taken prisoners, and he was in danger of starvation, until at length he was rescued from his perilous position, carried to one of the other houses, and again immured in the vault or chimney.

But of all the narrow escapes perhaps Father Blount's experiences at Scotney Castle were the most thrilling. This old house of the Darrells, situated on the border of Kent and Sussex, like Hindlip and Braddocks and most of the residences of the Roman Catholic gentry, contained the usual lurking-places for priests. The structure as it now stands is in the main modern, having undergone from time to time considerable alterations. A vivid account of Blount's hazardous escape here is preserved among the muniments at Stonyhurst—a transcript of the original formerly at St. Omers.

One Christmas night towards the close of Elizabeth's reign the castle was seized by a party of priest-hunters, who, with their usual mode of procedure, locked up the members of the family securely before starting on their operations. In the inner quadrangle of the mansion was a very remarkable and ingenious device. A large stone of the solid wall could be pushed aside. Though of immense weight, it was so nicely balanced and adjusted that it required only a slight pressure upon one side to effect an entrance to the hiding-place within. Those who have visited the grounds at Chatsworth may remember a huge piece of solid rock which can be swung round in the same easy manner. Upon the approach of the enemy, Father Blount and his servant hastened to the courtyard and entered the vault; but in their hurry to close the weighty door a small portion of one of their girdles got jammed in, so that a part was visible from the outside. Fortunately for the fugitives, someone in the secret, in passing the spot, happened to catch sight of this tell-tale fragment and immediately cut it off; but as a particle still showed, they called gently to those within to endeavour to pull it in, which they eventually succeeded in doing.

At this moment the pursuivants were at work in another part of the castle, but hearing the voice in the courtyard, rushed into it and commenced battering the walls, and at times upon the very door of the hiding-place, which would have given way had not those within put their combined weight against it to keep it from yielding. It was a pitchy dark night, and it was pelting with rain, so after a time, discouraged at finding nothing and wet to the skin, the soldiers put off further search until the following morning, and proceeded to dry and refresh themselves by the fire in the great hall.

When all was at rest, Father Blount and his man, not caring to risk another day's hunting, cautiously crept forth bare-footed, and after managing to scale some high walls, dropt into the moat and swam across. And it was as well for them that they decided to quit their hiding-hole, for next morning it was discovered.

The fugitives found temporary security at another recusant house a few miles from Scotney, possibly the old half-timber house of Twissenden, where a secret chapel and adjacent "priests' holes" are still pointed out.

The original manuscript account of the search at Scotney was written by one of the Darrell family, who was in the castle at the time of the events recorded.[1]

[Footnote 1: See Morris's Troubles of our Catholic Forefathers.]